Lab report write-up

The handout is lengthy, but please read all of the instructions. The handout contains specific details expected of your reports.

by Dr Mike Dohm Spring 2015 (updated 28 September 2020); revised and expanded from version written by Drs J. Cogbill and F. Kandel.

When you write a lab report, keep in mind that a person should be able to understand the entire experiment including the purpose, methods, data and conclusion even if this person never did the experiment him or herself. Style applies to the format of the manuscript as well as the writing content. For example, how should you cite a reference in your scientific paper?

Formatting styles are used to guide how the reference and citation to the reference should be handled. For formatting requirements, science journals adhere to a particular style and the prospective author must identify the style used by the journal before submitting a manuscript.

Biology journals often use APA Style or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS). Usually, when we write manuscripts we follow the often detailed instructions listed by the journal we intend to submit the manuscript to. Note, however, that the journals adhere to one of the general styles — the journals are not unique! So, learning the general issues and required elements of a style makes writing for different journal easier.

We will use the style guide for PLOS journals (e.g., PLOS ONE). PLOS journals adhere to the Chicago style. Formatting styles are used to guide how the manuscript looks, how it is organized. Although important, you as a student and author should focus most of your efforts to write better. Writing style — it is all about the content! You may have already been introduced to the idea of writing style and perhaps already been introduced to applying a required format style. For better writing, numerous style manuals have been produced: Strunk and White’s Elements of style, AP Stylebook, see Wikipedia Style guide page.

Writing styles are not just limited to grammar and spelling although these are important elements of good writing. You are not required to purchase a style guide for your Biology Lab assignments. However, as you are required to write a lot in college, Dr Dohm highly recommends that you choose and use a style guide as you write your lab report. The particular writing style described in the first sentence of this paragraph is called “classical style,” which is advocated by Steven Pinker in his recently published, excellent and accessible book called The Sense of Style: The thinking Person’s Guide to writing in the 21st Century. For more on classical writing style see this article in American Scientist. Strunk and White’s 1918 edition is in the Public Domain and available at http://home.ccil.org/~cowan/style-revised.html . Obviously, language and style has changed since 1918, so the link to that version is provided as a reference and not as an expectation for your to write like it is 1918 all over again! Back in my graduate school days I liked and used Day, R. A. How to write and publish a scientific paper.

Classical style is more than just deciding to use an active voice (“We recorded body mass to nearest 0.1 g of fish [n = 3] in 20 minute intervals”), instead of passive voice (“Body mass of fish [n = 3] were recorded to nearest 0.1 g in 20 minute intervals”). (For the record, Dr Dohm prefers active voice.)

The aim of classical style is to have a conversation with the reader. Do either of these two sentences tell the reader enough about what was actually done? How exactly does one weigh a fish? Was the fish weighed in a container with water and the difference the fish body mass recorded was actually the difference between the two? And what about “20 minute intervals?” Was the fish placed onto a scale for the duration of the experiment and at time 20, 40, etc. the mass was recorded or did the clock restart after each body mass recording?

The reader was not there for these decisions so you need to tell the reader what you did — and not make the reader guess! Clearly you don’t want to bore the reader with excessive detail. For example, “We used a balance that was located in the front of the lab room on a lab bench with black counter top,” is largely irrelevant information. Strive for balance in your science writing. Where exactly is this balance? Err on the side of providing too much detail, and not too little information.

Writing style guides how to write a paper. In addition to style, lab reports require that the writer adhere to a particular format called the IMRAD format, or Introduction, Materials and Methods, Results, Discussion. Format and style are not the same things, so you may need to add resources to your library for both. There are MANY resources on writing well in science for students — you can start at the University of Wisconsin’s Writing Handbook — Formatting Science Reports; Bates College Biology Department has a deadline-fast-approaching-friendly online guide to science writing at http://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWtoc.html. Again, we will use ICMJE style, so the online reference for this style is at http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/manuscript-preparation/preparing-for-submission.html .

An example student paper

To give you a sense of what is expected I include an example paper for you to look at.

Please use the example paper as a template or guide for how to put your manuscript together, not necessarily as a model for writing paper. For example, note that Tables and Figures are appended to the end of the document, not embedded within the body of the text. This is a standard way journals expect authors to submit there work.

Note: By the way, based on our rubric, this Student paper example would get a “B.” It’s not a bad paper, but it is an uneven paper (e.g., the Abstract misses key details). Importantly, not enough biology, i.e., paper failed to discuss the results in terms of consequences for development of the frog: the discussion should be more about lack of evidence that metamorphosis appeared to be metabolically neutral.

Simulated papers

Your Biology Lab Reports and Papers at Chaminade University are expected to include the following components:

The following guidelines are abbreviated and adapted from ICMJE for use by biology students at Chaminade University. These guidelines do not replace those of the more extensive ICMJE resource available to you.

1. Title: A title explains to the reader what the report contains. A title should not be so general that it does not specify what the experiment is, e.g., “Osmosis.” At the other extreme, the title should not be so long that it tells everything, e.g., “Osmosis using dialysis bags containing 0.5 M sucrose solution placed in isotonic, hypertonic, and hypotonic solutions with iodine…” It should sound professional and not tabloid- or popular-press like, e.g., “Scientists announce: Goldfish can survive in salt water!”. Be creative and imaginative to attract the interest of the reader. Do not use the title on the laboratory handout or from the laboratory text. The title is located on its own, separate page called the title page. The title page also includes the author name(s), date of the paper, and other relevant information for identification.

2. Abstract: An abstract is a brief, one-paragraph summary of the purpose and results of the experiment, usually no longer than 300 words. This type of abstract is termed “informative abstract,” and falls somewhere between the “descriptive abstract,” which is more typical in Humanities and Social Sciences and the “structured abstract,” which is the common format for medical research. The abstract precedes the introduction and is placed on its own page. and is indented.

For additional hints about writing an effective title and abstract see this resource at www.editage.com.

3. Introduction: This portion includes a full presentation of the objectives of the experiment. A literature review becomes important here. It also includes the biological concepts or principles on which the experiment is based and what is expected in the experiment (i.e. hypothesis). Include a brief review of evidence from previous experiments or known information from previous testing whenever possible. Two or three paragraphs should be sufficient for a lab report.

4. Hypothesis: Use a sentence stating the expected outcome such as “higher incubation temperature increases enzymatic activity”. Your hypothesis should be written in a sentence or two and should be included in your Introduction. Along with the hypothesis statement you should include clear predictions for the results of your experiment.

5. Methods and Materials: This section is perhaps the second most important component of a science paper. Materials used and description of the subjects. Here, you explain how the hypothesis was tested: you include a clear description of the experiment and data collection procedures. Methods, techniques, equipment/supplies used are included in this portion. You should include clear statements about how data were analyzed and evaluated to test your hypothesis. If calculations are involved, formula for calculation should also be included. Items such as lab coats, goggles, and gloves should not be included. You must include a description of the control and why such a control was utilized and explanations of deviations from original procedures. Do not copy instructions from your lab manual — instead, include a statement like “I used procedures provided in the Chaminade Biology 216L Lab manual (pp. 34 – 37), with the following changes.” Then, follow up with any changes from the published instructions. Do not write methods like a protocol.

6. Results: Arguably, the Results section is the most important component of a science paper. Present your experimental data in Results section in the form of sentences, numbers in tables or graphs. If you have one or at most a few numbers to report, report the numbers in a sentence or two. Tables are useful to present lists of numbers in situations where you want the reader to see the actual numbers (or at least a summary of those numbers) so that the reader can interpret the results for themselves. Your Results must include description — it cannot simply be a one sentence: “See Figure 1.” Do avoid making conclusions in Results. Your intent is to convey what you found, what you observed, and what happened. You may also use the Results to note any errors or departures from data collection procedures. Do not present your raw data as a table. It is advisable, however, to provide your raw data in an Appendix.

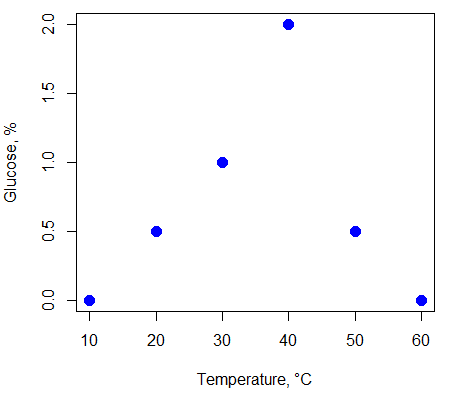

Do not report the same data in multiple formats. For example, if a sentence will do, do not also present the data in a table and then again in a graph. Choose one or the other — for our example of temperature and glucose production the graph would be the best choice as it shows the reader clearly the parabolic association between temperature and percent glucose in the solution.

7. Discussion: This is the most important part of a lab report. This portion discusses and explains the results of the research. It includes:

a. A thorough discussion of the results of the experiment. You will make reference to your figures and/or graphs.

b. A comparison of the results to the theoretical principles and what was expected.

c. Error analysis or plausible reasons for deviations.

d. Concentrate on errors of experimental design and instrumentation. Do not rely solely on technique errors, i.e., “the investigator titrated the wrong volume or did not obtain the correct weight.” Answers to questions asked by experiment should be incorporated into this section or in a separate section.

e. Discuss whether your experiment results agree with or reject the hypothesis. Do not say that your results “proved” a hypothesis!

8. Conclusion: An optional portion in which the investigator assesses the experiment by listing in short sentences the results. The conclusion can be the final paragraph in the Discussion section.

9. References: A part of the report that cites the works of others including journal articles and books used in the report. Tertiary references, such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, and Wikipedia are not acceptable references. You must cite works of others even if direct quotes were not used — if you do not, then you are guilty of plagiarism. If direct quotes are used, follow Standard English procedures. Citation in text follows the format of “author last name year,” for example “Pender et al 2014.” Use ICMJE (“Vancouver” format). Examples are

Standard (Print) Journal article

Pender RJ, Morden CW, Paull, RE. Investigating the pollination syndrome of the Hawaiian lobeliad genus Clermontia (Campanulaceae) using floral nectar traits. Am J Bot 2014 Jan 1;101(1):201-5.

Online Journal Article

Chen Y, Cairns R, Papandreou I, Koong A, Denko NC. Oxygen Consumption Can Regulate the Growth of Tumors, a New Perspective on the Warburg Effect. PLoS ONE 2009 Sep 15;4(9): e7033, accessed February 28, 2010, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007033

Book

Harasewich MG, Moretzsohn F. The Book of Shells: A life-size guide to identifying and classifying six hundred seashells. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010.

For other kinds of references and citations, e.g., web page or blog, see Sample References at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/uniform_requirements.html.

Formatting can be time consuming and frankly, it’s not a great use of our time. So I highly recommend you take advantage of available software assistance. For example, EasyBib is available as free add-ons to Google Docs and Microsoft Word. Once installed it is easy to generate a bibliography for your report by submitting your references to EasyBib, select the format (PLOS One), and let the software do the work for you.

10. Tables. Tables should be self-explanatory to the reader. Report each table in a separate page to follow after any Appendix (if used) or the References section. When using tables, make sure you include table title, variable titles, and units. The table title should be no longer than one sentence. In the following example, “Table 1. Temperature and glucose production” is the table title. “Temperature” and “Glucose” are variable titles. “°C” and “%” are units. In the text body of your report, direct the reader to the Table by enclosing in parentheses (Table 1). An example of a simple table follows. Noe that the title of this example table should be improved — “temperature and glucose production…” by whom? At a minimum, the title should include the subjects studied.

Table 1 Temperature and glucose production

| Temperature, °C | Glucose, % |

| 10 | 0 |

| 20 | 0.5 |

| 30 | 1 |

| 40 | 2 |

| 50 | 0.5 |

| 60 | 0 |

11. Figure legends. Figure legends provide context for the images, drawings, or graphs presented in the paper. For each figure provide a separate legend; group all legends on one (or more if needed) page; do not place a figure and its legend on the same page. In the following graph, “Figure 1 Temperature and glucose production in photosynthesis by algae” is the graph title.

12. Figures. Images, drawings, and graphs are all referred to as figures in science writing. Graphs are often the best way to help the reader see a trend. When using a graph to present your data, include labels and units for both x and y-axes., and legends presenting each test if there is more than one testing. In the following graph, “Temperature, °C” and “Glucose, %” are the labels and units for the x and y axes, respectively. There is no legend in this graph because there is only one testing. You should learn to use excel or other graphic software to plot your graphs.

Figure 1. Scatter plot of percent glucose by temperature, °C.

We do not expect you to produce perfect graphs. The graph above was created in R, the statistical programming language (which should be familiar to those of you in Data Science program or who have completed Biostatistics or Systems Biology at Chaminade University). For completeness, here’s the code

Temperature <- c(10,20,30,40,50,60) Glucose <- c(0,0.5,1,2,0.5,0) plot(Temperature,Glucose, col="blue", pch=19, cex=1.5, xlab="Temperature, °C", ylab="Glucose, %")

You can check out this code by running it at rdrr.io

But likely, most of you will use your spreadsheet app. Here’s some guidelines.

Again, we do not expect you to produce perfect graphs. For example, graphs with grid lines are rarely acceptable in a professional journal. However, we want your emphasis to be about content rather than following an exacting format. Thus, graphs made in a spreadsheet program like Google Docs or Microsoft (MS) Excel are acceptable. A simple option like Create a Graph online software at http://nces.ed.gov/nceskids/createagraph/ would also be acceptable for a report submitted to earn a grade for a biology course. We advise, however, that you look beyond expedient but generally poor quality tools like Create A Graph or MS Excel. These tools for graphics are not your only option and, indeed, seldom are best choices. A much better choice is available for free at https://plot.ly. The learning curve for plot.ly is shallow

13. Appendices are an increasingly important component of science papers, although generally only for the online version of the published article. Appendices are used to provide the reader access to information that, while not essential for the paper, serves to clarify points presented in the paper. Raw data and extensive, detailed protocol descriptions are often presented in appendices to avoid breaking the flow of the paper.

General procedures for the lab report

1. Your draft must be your best effort. No missing elements, no typos, give me your best grammar. The purpose of the draft is to provide the reviewer (Dr Dohm) what you would consider your final paper! You will receive suggestions for improvement from Dr Dohm, which are expected to be addressed in your final paper.

2. All work will be turned in electronically, in the form of a pdf file. Your instructor will provide the link and instructions needed to complete submission of your manuscript.

3. All manuscripts are to be prepared with a word processing app (e.g., Apple Pages, Google Docs, LibreOffice Writer, Microsoft Word). Handwritten reports are not acceptable. A reminder, I recommend EasyBib to help you format citations.

4. We expect you to adhere to PLOS ONE style. Document formatting instructions include:

-

- Use a standard font, Times New Roman, size 12 pt.

- Double-space all text, including title, abstract, figure and table legends and titles.

- Apply proper page margins: all margins 1 inch (top, bottom, left, right)

- Begin new pages by inserting page breaks, not by a series of “carriage returns” (i.e., hitting the Enter key over and over again to insert lines in the document until a new page is started).

- How long? The length of the manuscript is judged by Introduction + Methods+ Results+ Discussion= expected 1500 words (range 1350- 1650); that’s about 6 pages double spaced.

- No footnotes.

5. Two references, other than the laboratory handout, text, and lab manual are required and are normally used in the introduction and discussion section. Tertiary references are not acceptable references.

6. Grading of papers is based on use of proper format and procedures, organization, and interpretation. Grammar and spelling are also evaluated as part of your grade. See rubric for lab report

7. Sometimes it is required that data from the entire laboratory section be pooled or used, it is your responsibility to obtain the results from other students or groups.

8.