Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Background

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a technique which is used to amplify the number of copies of a specific region of DNA for a relatively small DNA molecule (up to a few thousand bases long). “Polymerase” refers to a DNA polymerase, the holoenzymes responsible for DNA synthesis (replication). In principle, millions of copies of the desired sequence may be amplified from even a single initial copy. PCR consists of repeated cycles of heating and cooling of a reaction containing DNA template in the presence of a DNA polymerase and substrates (dNTP). Heating the reaction to near boiling permits DNA melting of the DNA strands (breaking of H-bonds); cooling the reaction permits DNA annealing of Watson-Crick compatible DNA strands. Primer sequences provide the specificity of the PCR reaction, allowing for the amplification only of the target DNA sequence. PCR is an incredibly powerful technique, now widely spread in biology research (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. NGRAM results for books scanned by Google for “microscope,” “electrophoresis,” and “PCR”.

The basics

There are so many descriptions of PCR, so many opinions, that it seems almost silly to cite a particular presentation. Do read the presentations in your textbooks, but then a nice, recent overview is presented in Garibyan & Avashia (2013). PCR is a technique you should be very much educated about.

With respect to methods, there are many excellent animations of PCR available, ranging from very basic to more advanced. Here’s an overview video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-FrjxAnx0Y

I also recommend you know something about the history of PCR discovery. For example, a short history of the Polymerase Chain Reaction, by Bartlett and Sterling (2003). For a more comprehensive history, see the book, Making PCR: A story of biotechnology, by Peter Rabinow.

Given a DNA sequence as template, a set of primers designed to frame a target sequence within the DNA sequence, a thermal-tolerant DNA polymerase, plus substrates and supporting chemicals, PCR involves 30 or more repeats of three basic steps:

- Denature or melting the double stranded DNA (dsDNA) to single strand DNA (ssDNA).

- Annealing between primers and target ssDNA

- Synthesis of new DNA by DNA polymerase

The denaturing step is relatively straight-forward. The reaction is brought up to 94 – 95 °C for a short (30 sec) or longer time (several minutes in some cases).

During the annealing step, the thermalcycler temperature is brought down to about 60 °C. The annealing temperature is the temperature at which the primers will anneal, form hydrogen bonds according to Watson-Crick pairing, to the target sequence. Annealing temperature is related to the melting temperature, Tm, for DNA, which in turn is related to the base composition of the DNA. The Tm for an oligo is the temperature at which 50% of the single strand oligos have formed double-strand pairings. DNA sequences with lots of G and C will have a higher Tm than a sequence of same length, but containing higher percentage of A and T. After obtaining the Tm for your oligos, the recommendation is to subtract 5 °C (4 – 6 °C) to obtain the predicted annealing temperature.

As a simple rule of thumb you can predict the Tm for a primer sequence as follows. Count the GC content and the AT content of the sequence. Multiple the frequency of (G+C) by four, the frequency of (A+T) by 2, add these up, and that will be a pretty good estimate of the melting temperature.

For example, consider the 20mer sequence: GTATGCGAGATCGATAGATT. The GC content is 40%; the AT content is therefore 60%. From our formula we predict that the Tm is about

and our annealing temperature would be 51 C (= 56 – 5). This simple Tm equation compares favorably to more sophisticated algorithms (e.g., 54.3 C, obtained from salt-corrected calculations provided at http://biotools.nubic.northwestern.edu/OligoCalc.html).

Choosing the correct annealing temperature

See Rychlik et al (1990).

How many cycles?

The three steps of PCR are repeated between 20 ad 40 times to amplify target DNA. How many cycles depends both on target yield and amount of starting template DNA. If starting template DNA concentration is high, then fewer cycles are needed to obtain a reasonable target yield. If, however, template DNA is low to start, then more repeats of the three steps (i.e., more cycles), will be needed. However, after 40 cycles the risk of non-specific amplification increases.

The synthesis step is simply DNA replication.

PCR variants

PCR directly amplifies the target DNA, yielding millions of copies of the targeted sequence (the amplicon). For example, we use PCR routinely to make cDNA from mRNA and to amplify the cDNA for my gene expression studies. We also use a variant of PCR called Q-PCR to quantify target expressed genes. Our lab also uses PCR for marker studies, and it is in this sense we will use PCR in genetics lab.

Here is a very brief list of the kinds of PCR techniques people use

- Ligation-mediated PCR: uses small DNA linkers added (ligated) to DNA sequence of interest: commonly used in DNA sequencing of long fragments of DNA (“primer walking“).

- RT-PCR, reverse transcription PCR: method to amplify isolate or identify a known sequence from RNA isolated from cells.

- RT-qPCR, Quantitative or Real-Time reverse transcriptase PCR (sometimes referred to as RT2PCR): method to quantitatively measure the amount of a DNA, cDNA ,or RNA from a sample.

- Allele-specific PCR (e.g., BI-PASA): technique to identify SNPs.

- Colony PCR: small amounts of cells are placed directly into the PCR master mix and, following a short, 100 C denaturing step, PCR is performed.

PCR has limitations

For one, the key to specificity lays in the design of the primers. Another limitation of PCR is that even with well-designed primers, long templates may fail to amplify. For longer fragments, cloning, the other technique for amplifying technique is used. Cloning involves cutting target DNA from a donor, inserting the target DNA into a vector (e.g., plasmid), then selecting the vector and growing the bacteria to amplify the target DNA.

One of the strengths of PCR, is also its weakness. In order to use PCR, one must already know the exact sequences on either ends of the gene (and for both strands) or other region of interest in DNA (flanking sequences). On the other hand, you do not need to know the intervening sequence (even though you are interested in that particular gene!). Fortunately, the DNA sequences of many of the genes and flanking regions of genes of many different organisms are already known.

So, if the sequence in one strand is: TAAAGGCCCACAGGATA [sense sequence of GOI] TTTTAACGCGCCCTATT

then the complementary strand would be: ATTTCCGGGTGTCCTAT [anti-sense sequence of GOI] AAAATTGCGCGGGATAA

Flanking sequences serve as primers for PCR

We are interested in amplifying a gene (or any particular sequence). Imagine we know that the above sequences flank the gene. For convenience I have noted the gene of interest (GOI) in red to indicate a long sequence whose precise identity we do not need at the moment. If we can also know that these flanking sequences are unique to our target gene, then these flanking regions would be our targets for PCR.

The first step for PCR would be to synthesize primers of about 20 letters-long, using each of the four letters, and a machine which can link the letters together in the order desired – this step is easily done, by adding one letter-at-a-time to the machine (DNA synthesizer). (Note that we love our shortcuts and acronyms in science — so, instead of saying a sequence that is 20 base pairs long, we say “20 mer” instead.) Now, a primer is a nucleic acid strand (oligonucleotide) that serves as a starting point for DNA replication.

Primers are required because DNA polymerase, the enzyme that catalyzes the replication of DNA adds DNA nucleotides only to existing sequences. In the old days, one needed to be able to make primers yourself, and it is not technically that difficult anymore, but a variety of companies now are set up to do this, and can do it at rapidly, at reasonable prices, and with high quality. I order primers from Eurofins MWG Operon.

In our example, the primers we wish to make will be exactly the same as the flanking sequences shown above. We make one primer (forward) exactly like the lower left-hand sequence, and one primer (reverse) exactly like the upper right-hand sequence, to generate:

TAAAGGCCCACAGGATA[sense sequence of GOI]TTTTAACGCGCCCTATT

ATTTCCGGGTGTCCTAT……..>>

and

<<…………TTTTAACGCGCCCTATT

ATTTCCGGGTGTCCTAT[antisense sequence of GOI]AAAATTGCGCGGGATAA

the “>>” shows the direction in which the sequence would be extended. At least in principle, it does not matter how long the intervening sequence is. With proper selection of primers, the upper DNA strand could be extended to the right in the direction of the arrow, and the upper right-hand sequence paired to the lower strand could be extended to the left in the direction of the arrow. Thus, we would exactly duplicate the original gene’s entire sequence.

After one cycle, there would be four strands, where originally there were only two. If we continue, then after two cycles, there will be eight strands, after three cycles, we have 16, etc.. Therefore, 30 cycles theoretically will yield approximately one-billion copies of the original sequences 230).

Thus, with this amplification potential, even tiny amounts of DNA can be amplified, hence the utility of this approach for forensics as well as for biomedical research. Consider that a single human hair follicle, which may contain a few shed epithelial cells, will be enough to use PCR approaches to work with human DNA.

Primer design

As you can well imagine, designing primers is not that easy. We will touch on some of the issues as we proceed, and we will attempt to design primers during the remaining time we have this semester. Briefly, here are some of the relevant issues we need to consider.

We need primers to be specific to a particular region to avoid hybridizations between undesired sequences. That is why primers are usually about 20 bp long — the probability that random sequences would hybridize is very low (420); we expect that any random 20 base-pair sequence will match our sequence only once every 1.1 x1012 times.

Other issues relate to making sure that the primer does not self-hybridize and that it anneals at high temperatures. We will return to these issues in our discussion of Primer Design.

Working with primer stock solutions

By now you’ve been at least introduced to a working lab environment, whether it is genetics or cell biology or chemistry, a basic message all of your instructors have imparted is to be cognizant of good housekeeping in the lab. Put another way, we work to avoid contamination. Contamination of our samples, contamination of our solutions. Thus, we commonly manage “stock solutions” and “working solutions.” Maintaining primer solutions is really important — obviously — so I wanted to relate some practical tips you can use later.

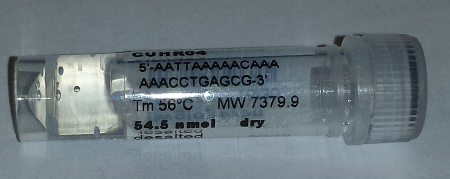

Figure 3. Vial from EuroFins containing primer sequence.

The vendor tells us how much DNA is in the vial. In this case (Fig. 3), 54.5 nM (54.5 nanoMoles). We reconstitute them to 100 µM/L (microMoles/liter) for our stock solution and aliquot to create 100 uL of working solution at 10 pM/L. Freeze the aliquots and bring them out as needed.

Next up

- Overview of standard PCR

- Overview of RTqPCR

- PCR Troubleshooting

- Primer design: Primer design with Primer3

See for questions about PCR

ccc

Additional Reading and References

Your text books

Brown, T. A. (2018). Genomes 4, (pp. 38-41). New York: Garland Science.

Klug, W. S., Cummings, M. R., Spencer, C. A., & Palladino, M. A. (2015). Concepts of genetics (pp. 498-4501). Boston: Pearson.

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polymerase_chain_reaction

Articles

Bartlett, J. M., & Stirling, D. (2003). A short history of the polymerase chain reaction. In PCR protocols (pp. 3-6). Humana Press. — pdf link

Breslauer, K. J., Frank, R., Blöcker, H., & Marky, L. A. (1986). Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 83(11), 3746-3750. — link

Garibyan, L., & Avashia, N. (2013). Research techniques made simple: polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The Journal of investigative dermatology, 133(3), e6. — link

Ponchel, F., Toomes, C., Bransfield, K., Leong, F. T., Douglas, S. H., Field, S. L., … & Robinson, P. A. (2003). Real-time PCR based on SYBR-Green I fluorescence: an alternative to the TaqMan assay for a relative quantification of gene rearrangements, gene amplifications and micro gene deletions. BMC biotechnology, 3(1), 18. — link

Rabinow, P. (2011). Making PCR: A story of biotechnology. University of Chicago Press.

Rychlik, W. J. S. W., Spencer, W. J., & Rhoads, R. E. (1990). Optimization of the annealing temperature for DNA amplification in vitro. Nucleic acids research, 18(21), 6409-6412. link